How to Improve Emotional Self-Regulation Among Children with Autism and Attention Disorders

Does your child get distracted easily and need to be repeatedly reminded to complete a simple task? Does their room look like it’s been hit by a tornado and they are constantly misplacing personal items? Do they have emotional outbursts when plans suddenly change?

For parents, many of these behaviors may seem familiar. But many typically developing children are able to improve their self-management skills, or executive functions, as they grow older and take on more responsibility. Some, including children diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyslexia, traumatic brain injury and other learning disabilities, have a harder time and may face executive function deficits.

What Is an Executive Function?

Traditional definition: The chief operating system located in the prefrontal region of the brain used to engage in cognitive processes required for goal-directed behavior.

What this actually means: Everything that you do every day to manage your own behavior.

Common executive function processes for goal-directed behavior include:

- Working memory

- Task initiation

- Sustained attention

- Inhibition

- Flexibility

- Planning

- Organization

- Problem solving

Although executive functions are often thought of as brain functions, Dr. Adel Najdowski, director of the Master of Science in Behavioral Psychology program at Pepperdine University, says all executive functions involve behavior. Therefore, individuals with deficits may be able to learn specific behaviors to improve their executive function performance. In her recently published manual, “Flexible and Focused: Teaching Executive Function Skills to Individuals with Autism and Attention Disorders,” Dr. Najdowski, who also teaches with the OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine program, outlines principles, procedures and activities that practitioners, educators and parents can use to improve the executive function skills of learners with deficits. This lesson is an adaptation of one section in her book on emotional self-regulation. For more detailed explanations on each lesson, read Flexible and Focused: Teaching Executive Function Skills to Individuals with Autism and Attention Disorders

What Is Emotional Self-Regulation and Why Is It Important?

Emotional self-regulation is the ability to adapt behavior when engaged in situations that might provoke emotions such as stress, anxiety, annoyance and frustration. A person with strong emotional regulation skills can:

- Notice when they become emotionally charged.

- Consider the consequences of their response.

- Engage in activities that move them toward their goal, even if they are feeling negative emotions.

Alternatively, a person who lacks emotional self-regulation may:

- Overreact to situations when compared to same-age peers.

- Experience negative emotions for a longer amount of time than same-age peers.

- Have a short temper and engage in emotional outbursts.

- Have mood swings.

Lesson: Teaching Emotional Self-Regulation

Before beginning the lesson, it’s important to note that the child should already be capable of identifying and labeling emotions. The activities should be initiated when a child is in a good mood. This lesson is also meant to be taken in stages with the child moving to the next step after they have successfully developed a mastery of the preceding step.

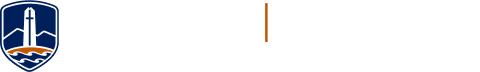

1. Create an emotional levels chart.

Create a visual aid that depicts the different levels of emotions that a child may feel, allowing the child to create their own labels for each level. For example, levels can be labeled “feeling good,” “a little upset,” “upset” and “very upset.” The chart should have two columns with the emotional levels in one column. Title the other column, “I feel this way when…” and leave the rows blank for the child to fill in.

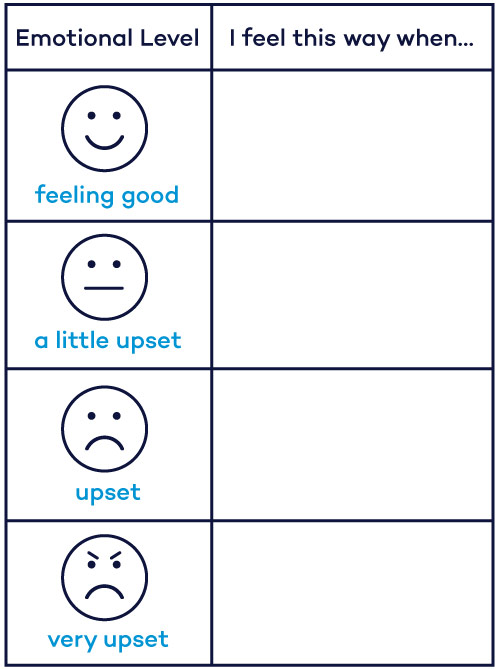

2. Teach the child to assign emotional levels to certain situations.

The person working with the child can prompt them in a number of ways. Ask the child to write down different situations that make them feel specific emotional levels. Another option is to present a scenario and ask the child to identify how that situation would make them feel. For example, ask the child how she would feel if she wasn’t allowed to wear her favorite shirt and instruct her to fill in the blank space next to the corresponding emotion.

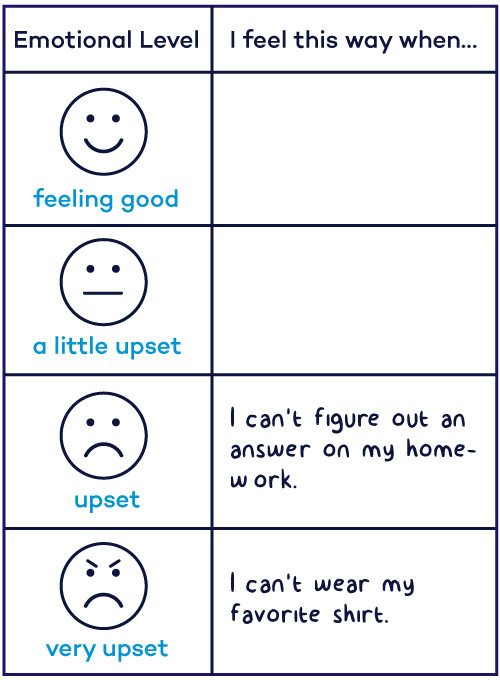

3. Talk to the child about what appropriate reactions should be to different scenarios.

Use the scenarios in the emotional levels chart to identify what should be treated as a big deal and what should be brushed off. For example, talk to the child about how not being able to wear your favorite shirt should make you a little upset, rather than very upset.

4. Teach the child coping strategies.

Identify strategies that children can use when they are feeling upset or very upset and practice the strategies. Give the child hypothetical situations and role-play how to use those strategies.

Coping Strategies

Taking deep breaths

Counting to 20

Asking for help

Talking to a friend

Thinking of a compromise

Walking away

Letting it go

Thinking of something that makes the learner happy

6. Practice coping strategies in a natural environment.

After the child has learned how to cope with a situation with advanced notice, ask them what they will do if the situation arises in real life. Remind them that they should always be prepared for the possibility that a situation will arise.

7. Measure the effectiveness of the intervention.

Use a graph to plot how often the child provides the correct response over time. The criteria for success may be different at each stage. For example, in the first stage, you may measure how often the child correctly identifies situations that make a child feel a specific emotional level. Once the child is able to score at least 80 percent across multiple sessions, you may begin the next stage. Measure for the following criteria:

Criteria to measure for:

- Correctly identifies situations that make the child feel an emotional level—across two to three sessions.

- Correctly identifies situations that are a big deal versus not a big deal—across two to three sessions.

- Correctly role-plays coping mechanisms—across two to three sessions.

- Successfully implements coping mechanism when warned about a difficult situation—across three to five sessions.

- Successfully implements coping mechanism when not warned about a difficult situation—across three to five sessions.

Remember:

This lesson is not meant to replace meaningful consequences for a child’s behavior. Children who react negatively to situations should not get what they want. Children who are able to use the discussed coping mechanisms should gain access to reinforcers. Reinforcers vary from child to child and can include praise or more tangible assets like candy or stickers. Children should not have regular access to reinforcers throughout the day, and you should make certain the child wants to earn the reinforcer and has not become bored with it. If the child is not responding to the reinforcer, you may also consider whether you need more continued reinforcement or whether you should be reinforcing more quickly after a positive response.

Citation for this content: OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine, the online Master of Science in Behavioral Psychology program from Pepperdine University.