Behavioral Addiction Recovery: A Guide for Families, Friends, Colleagues, and Roommates

In Hollywood’s version of reality, addictions are easy to spot. A character fumbles with a needle. Empty bottles decorate the dark rooms of a neglected apartment.

But in reality, addictions can be subtle, insidious, and all the more dangerous for their deceptive nature. This is particularly true of behavioral addictions, in which an individual is addicted to a behavior—such as shopping or working—that many of us complete every day without a hitch.

A behavioral addiction, sometimes called a process addiction, is characterized by the compulsion to continually engage in a behavior or activity, despite negative consequences.

A person addicted to shopping might, for example, spend hours online each day buying items they cannot afford. Packages pile up on their doorstep, debt accumulates on their credit card, their family misses them—but they cannot stop.

Many different kinds of behavioral addictions exist. Some of the most common include:

- Communications and social media

- Exercise

- Food

- Gambling

- Gaming

- Love

- Pornography

- Sex

- Shopping

- Work

Why Do Behavioral Addictions Happen?

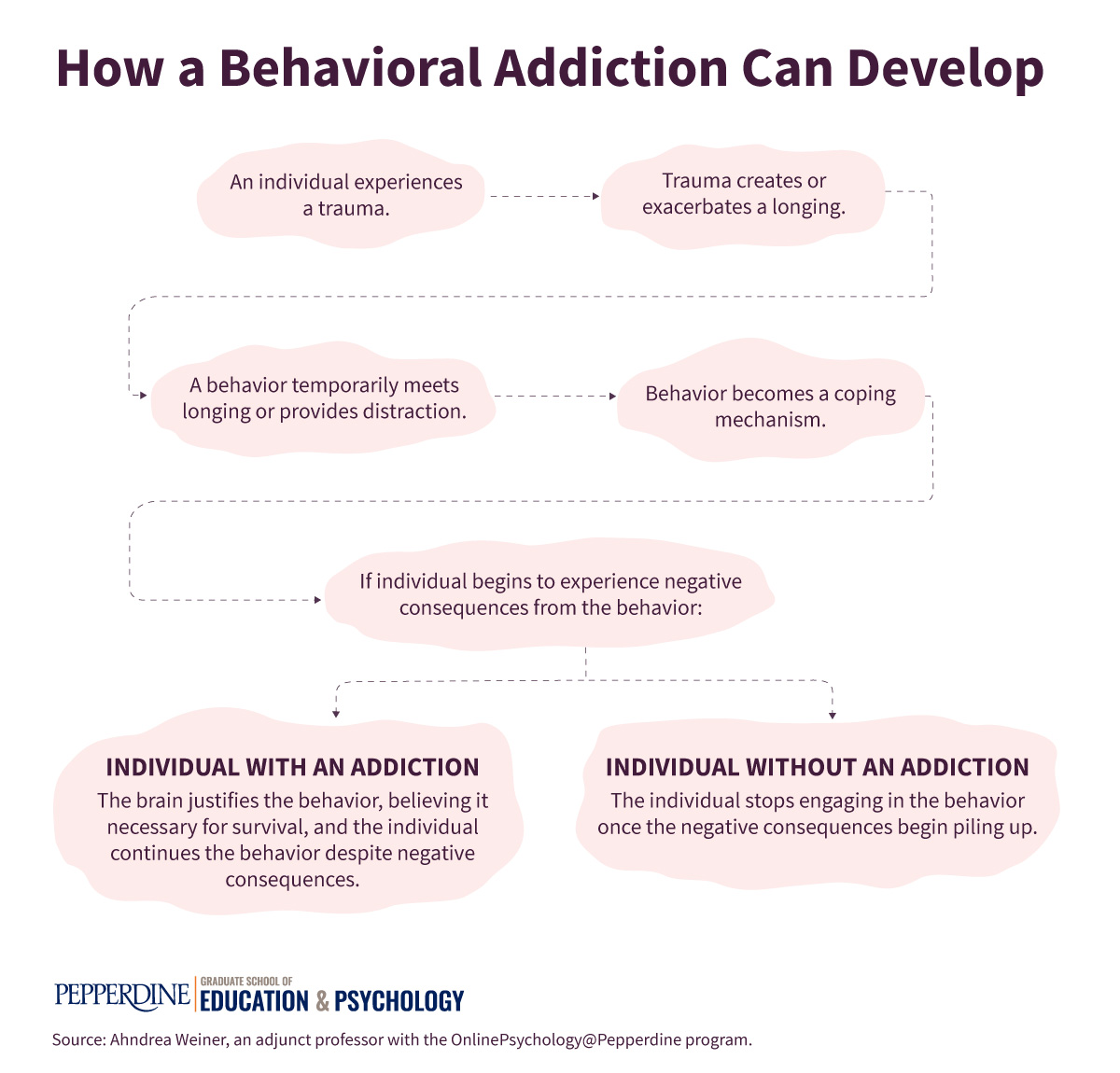

A behavioral addiction can often be traced back to a traumatic experience, explains Ahndrea Weiner, an adjunct professor with the OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine program. When a person has experienced a death or divorce in the family, they long for an escape from the pain. They do something—go shopping, play a slot machine, or test a new video game—and receive pleasure from the behavior.

At the heart of an addiction is an emotional, spiritual need…Identifying the need and finding a healthier way of meeting it is essential to recovery.

The behavior gradually becomes a coping mechanism, said Weiner, who also teaches on campus and serves as director of training and clinical supervisor at the Matrix Institute on Addictions. Eventually, the brain begins to change its reasoning to justify the behavior, despite negative consequences: If [insert behavior] feels good, then I must need it. If I need it, the behavior must help me survive.

According to Weiner, once the brain connects the behavior with survival, through hit after hit, the limbic brain—the area of the brain associated with basic survival—takes over brain function from the cerebral cortex. The cerebral cortex is the brain’s judgment center, which handles reasoning and rational thinking. In an individual without an addiction, the cerebral cortex would decide to stop engaging in the behavior once the negative consequences began to pile up: bills, relational stress, physical exhaustion. But individuals with addictions cannot stop, because their brains have been rerouted to believe the behavior is necessary for survival.

Put another way: At the heart of an addiction is an emotional, spiritual need. This could be the need to feel powerful and in control, to feel beautiful, to feel less lonely, to escape pain. Identifying the need and finding a healthier way of meeting it is essential to recovery.

Addiction is not really about the behavior, explains Cam Adair, founder of Game Quitters, a support community for video game addiction. “It’s not about the games,” he said. “It’s about why you play the games. If you can understand why you play the games, you can move on from them.”

But first, we need to be able to recognize the symptoms and diagnose the problem.

Make a Difference in Addiction Recovery

What Is the Difference Between a Healthy Habit and a Behavioral Addiction?

Because behavioral addictions often encompass everyday behaviors, they can be difficult to spot and understand.

According to American Addiction Centers, a behavior is not labeled an addiction unless the following are true:

- The person struggles with mental health or physical health issues as a consequence of the behavior and/or the inability to stop.

- The person has difficulties in significant relationships at home and, in some cases, at work because the behavior is so disruptive.

- The person experiences other negative consequences that are directly caused by continued, extreme, or chronic engagement in the behavior.

- The person is unable to stop engaging in the behavior despite these consequences.

How to Support Someone in Recovery

Even if the symptoms are obvious to you, the people you care about may not understand that they have an addiction. Until they come to this realization on their own, Weiner says, very little you say is likely to make them change. Natural consequences can be the most effective teachers.

Once your family member, friend, roommate, or colleague begins to express a desire to change, then you can step in with support. These statements sound like: “I need help,” or “Can you help me find a therapist?”

Professional and community support are often crucial to addiction recovery. You can help your loved one find support or a trusted professional. Offer to get together in a safe, neutral space to research options in your community.

Recovery can be grueling, and everyone will differ in terms of the support they need and how long the process takes. Try asking your friend, family member, or colleague how you can help, and understand that they may not be able to answer you right away. The crucial action for you to take as a support person is reaching out your steady hand.

10 Ways to Support Someone Recovering from a Behavioral Addiction

1. Open the dialogue.

Let your person in recovery talk about what they are going through. Allow for vulnerability and avoid making judgments.

“A lot of us are dealing with this alone, and I don’t think anything diffuses shame more than speaking about it,” said Erica Garza, author of Getting Off: One Woman’s Journey Through Sex and Porn Addiction.

Weiner offers this reminder to families and friends: If you tell your loved one that they can be honest with you, be prepared to hear stories that may shock you. Be ready to experience how insidious an addiction can be.

2. Learn and process together.

An addiction involves not only the individual but also their close community. The whole family or even intimate friends need to go through the healing process, too.

Instead of expecting your loved one to carry the weight of recovery alone, ask yourself: “How can the whole family take this addiction on?” Or, “How can our whole friend group provide support?”

See a therapist if you can afford it, or join a moderated support group. (See the recommendations listed below). Trained professionals can help you support your loved one’s recovery by working on communication patterns, processing feelings of guilt, and setting boundaries.

Offer to attend a 12-step meeting or therapy session with your loved one to better understand their experience.

3. Don’t come to the rescue.

Weiner explains that friends and families, in particular, want to solve their loved one’s problems and shield them from the consequences of the addiction. However, this kind of behavior actually supports the addiction.

Instead, Weiner recommends setting parameters that demonstrate love and accountability. Vocalizing these might sound like: “I love you, but I cannot finance this addiction,” or “You can live here, but I do not want you to play video games in my house.”

4. Take up a new activity together.

Do something together that does not involve talking about the addiction. Learn to play chess, try a new recipe for cinnamon rolls, go to hockey games, or find new books at the library.

You might have an opportunity for intimate conversation, but that is not your primary goal. Adair of Game Quitters explains that this time is about developing trust and rapport. That way, when difficult conversations do need to happen, you will have cultivated a better connection.

5. Change the environment.

Getting out of the house can relieve built-up pressure and tension. You don’t have to go far—just far enough away from any places that trigger your loved one’s addiction.

Go for a drive or take a walk around the neighborhood. Both scenarios allow you to talk side by side instead of face-to-face, which can ease the anxiety around being vulnerable.

6. Check in.

Friends and family often say, “If you need anything, I’m here.” While helpful, this kind of message puts the burden on the person in recovery to ask for support. And unfortunately, individuals recovering from addiction are often less likely to reach out for help when they need support the most.

Put the onus on yourself instead by calling or sending a message with an open-ended question, such as “How are you doing today?” Be prepared to hear the answer, positive or negative.

Or, offer a supportive voice: “Hey, I’m here, and I’m thinking about you.”

7. Follow up after checking in.

If a loved one tells you today they are not doing well, follow up tomorrow. Ask: “How was today? Are you feeling any better?”

Your consistency will reassure the person that you remember and you care. As much as possible, avoid checking in once and never again. Also, remember that looking up someone’s social media does not replace a personal connection.

8. Notice addictive patterns and gently point them out.

If you notice unhealthy patterns starting to creep into your loved one’s behavior, consider pointing that out. Be calm and gentle. Avoid making judgmental statements about the behavior (e.g., “I see you exercising three times a day, and you shouldn’t do that.”)

For example, if you notice your friend always spends an hour shopping online before health appointments, flag that behavior for them. Suggest an alternative activity to do together: “Before you go to the doctor, maybe you and I can go out for a walk instead and talk about how you feel. Or, we can just relax.”

9. Try not to be the “addiction police.”

April Benson, a psychologist who treats compulsive buying disorder and author of To Buy or Not to Buy: Why We Overshop and How to Stop advises family and friends not to become the addiction police. Monitoring addictive behaviors—whether bank statements, time online, or cell phone data usage—can come across as punitive, not supportive.

For someone who is receiving therapy, you can trust that the therapist is helping them develop healthy boundaries and positive goals toward recovery. You do not need to cross-examine them or second-guess their actions.

Instead, ask them about the goals they are working on. Encourage them and offer support if and when they want it.

10. Care for yourself, too.

Some family members and close friends are disciplined enough to process their loved one’s addiction on their own. However, many more need professional guidance. Weiner recommends receiving therapy or attending a support group separate from the individual’s treatment.

You can try this therapeutic exercise on your own:

- Family members and friends often say they feel guilty about the addiction.

- Ask yourself: Is guilt the most accurate word for what you are feeling? If you did the best you could, can you really feel guilty about that?

- If your answer is no, ask yourself what is a better word: disappointment or sadness, fear or pained?

Sources:

Ahndrea Weiner, adjunct professor, OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine program

Erica Garza, author, Getting Off: One Woman’s Journey Through Sex and Porn Addiction

Cam Adair, founder, Game Quitters support community for video game addiction

April Benson, psychologist and author, To Buy or Not to Buy: Why We Overshop and How to Stop

Further Reading and Resources

Eating Disorder Hope: Weekly Hope with Kirsten Haglund

Game Quitters: Parent Support Group

Game Quitters: Video Game Addiction Resources for Parent and Loved Ones

Mental Health America: Find Support Groups

National Alliance on Mental Illness: Family Members and Caregivers

National Council on Problem Gambling: Programs and Resources

National Institute of Mental Health: Help for Mental Illnesses

Stopping Overshopping: Archives for Friends and Family

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Find Help and Treatment

Prepare for a Career in Addiction Counseling

Citation for this content: OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine, the Online Master of Psychology program from Pepperdine University.